The third time I wound up in the emergency room struggling to breathe, I started to consider my mortality.

When I was a child, asthma landed me in an oxygen tent for a week. As an adult, when even my rescue inhaler and nebulizers couldn't help my lungs, I unconsciously started writing my own obituary.

I tried not to think about death. But it always lingered, in a spooky, dark corner of my mind.

Americans largely don't talk about death, as if mentioning it would summon the Grim Reaper. In a survey conducted in April by Chapman University, 29% of respondents indicated they were afraid or very afraid of dying. A 2013 article in Psychology Today described death as the US's "leading source of uneasiness, discomfort, and apprehension."

My Spanish class showed me how to celebrate

There's no better time of year to witness our culture's fear of death than during Halloween, when we adorn our yards with skeletons, mummies, and zombies.

In my Spanish classroom, however, we observe differently.

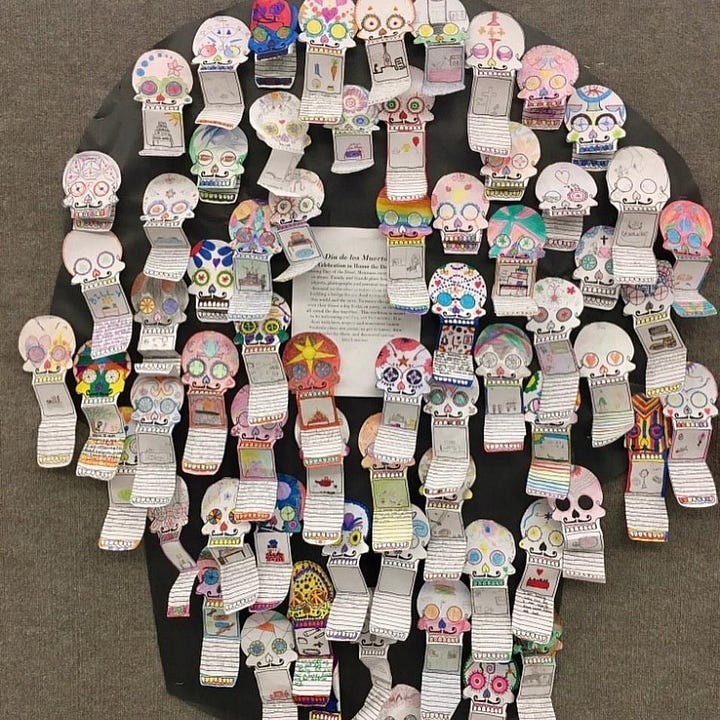

This time of year, my classroom floor is covered in glitter and brightly colored feathers. My students are putting the finishing touches on their sugar skulls for Día de Muertos, which falls on November 1 and 2. In Mexico and around the world, people remember loved ones who have passed on with altars, marigolds, photos, offerings, and celebrations.

As a Spanish teacher, I started introducing my students to Day of the Dead about five years ago. We learn about how the Day of the Dead is celebrated in Mexico and make skeleton puppets, sugar skulls, or altars. I ask my students to think of a loved one who has died and draw an altar for them. We sit in a circle and talk about which artifacts we would place on an altar to conjure our loved ones for a night of fiesta.

Mexican tradition holds that the dead would be offended by grieving and sadness so the festivities should be joyful and full of laughter.

The Mexican poet Octavio Paz once said: "To the people of New York, London, and Paris, 'death' is a word that is never pronounced because it burns the lips. The Mexican, however, frequents it, jokes about it, caresses it, sleeps with it, and celebrates it. It is one of his favorite toys and most steadfast love."

COVID-19 made me reconsider things

Then COVID-19 came. Knowing that a respiratory disease could put me at greater risk of illness or even death, I considered the possibility that I could die tomorrow.

Death no longer felt like a spooky shadow that needed to be avoided. It had always been there, always would be. But that shadow was now adorned with flowers and color and photos of loved ones.

Psychologists talk about naming, confronting, and reframing our fears to help us overcome phobias. By allowing the brain to get used to a feared object or situation, we can adjust how we respond.

Carlos Olmedo, the director of the Dolores Olmedo Museum, explains it this way: "For Mexicans, death was part of life. For us, it was like going from day to night so we didn't feel something we were losing; it was just a step more."

Celebrating Día de los Muertos with my students and children has helped me reframe how I view death and dying. It no longer feels like something separate from life but as something that's connected, just as the day and night are connected — no longer a loss, but another step.

This essay originally ran on Insider Magazine on October 31, 2022

I love that: "going from day to night"! Somewhere along the way, some of us, many of us divorced ourselves from the cyclical nature of life-death-rebirth and forgot that death is only a season in the story, not the end. Thank you for sharing about your personal fears, which are quite understandable, and for how you have learned to celebrate the night.

I like what u do with your spanish class to make them aware of the celebrations of day of the dead. The spanish teacher in the high school I sub at, and used to teach at, does this as well. I am sure it is helpful for kids to be aware of how death is treated by other cultures !