Making friends with our monsters

The health benefits of speaking your truth + wisdom from Melissa Febos & Bayo Akomolafe

Friends,

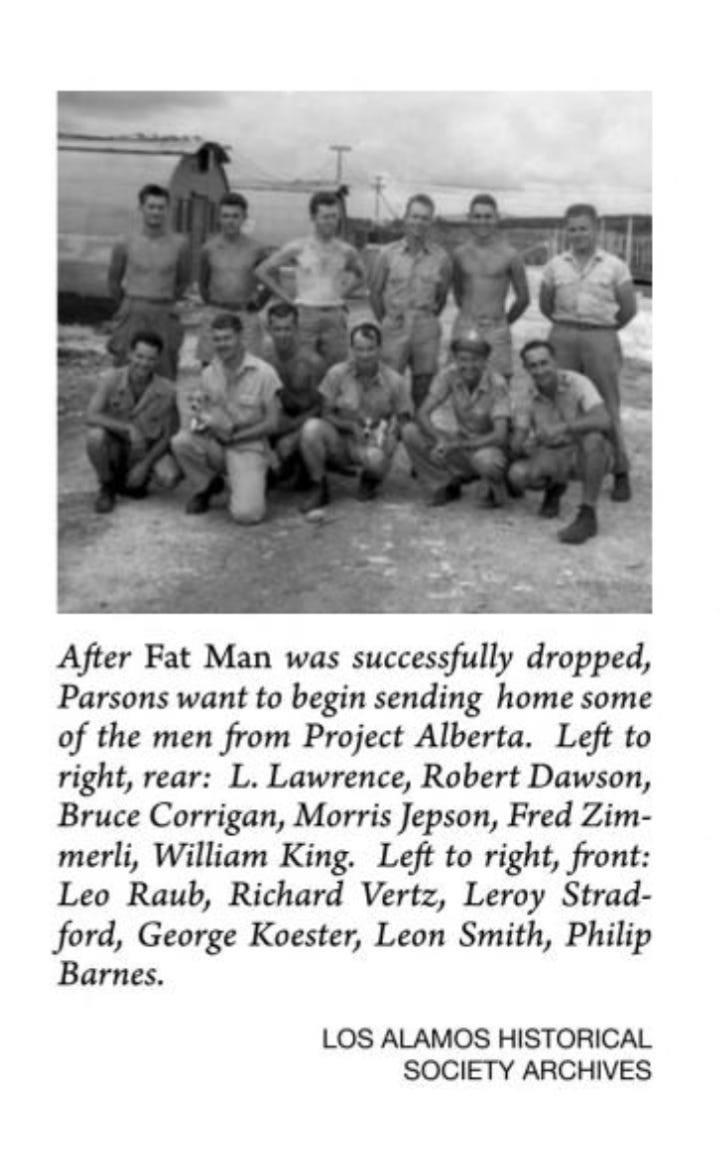

I just watched Oppenheimer, and let me tell you, I had FEELINGS. My grandfather worked on Project Manhattan and served in the 1st Ordnance Squadron at Los Alamos. A math genius, he tinkered on the atomic bomb while my dad, only ten months at the time, learned to crawl while living at the top-secret atomic bomb factory.

The plane that dropped the bombs was too heavy to get off the ground safely if the bomb was armed, so my grandfather was one of three men charged with arming it on the plane. Three bombs, five men. Each man drew a straw. The one who drew the shortest straw would drop the first bomb. The second shortest length would drop the second, the third shortest, the third.

My grandfather drew the third shortest straw. But Japan surrendered after the second bomb was dropped over Nagasaki, so there was no third bomb.

I never met my grandfather and didn’t know about Los Alamos until I saw the movie. My dad describes my grandfather as “a very spiritual man” who believed the atomic bomb saved millions more lives. Yet, he never talked about it. My dad still hasn’t watched the movie.

There’s a part in Oppenheimer the movie that gave me chills. It’s where Oppenheimer says, “This job is hard for your heart.”

At the age of 62, my grandfather had a fatal heart attack in his sleep.

My dad named me Summer. Maybe living in the cold rainforest of Juneau, Alaska, my name reminded him of his home in San Diego. Maybe he imagined me warm and cheery, like Californian sunshine.

Sometimes, though, I am not very summery. Often, I am more like autumn or winter.

What makes me warm again is complaining and beseeching allies that can help me hold my shit. “Ugh, that sucks,” or “damn, I’m sorry” works wonders. Likewise, when my daughter has a meltdown, the only way to get her through is to hold her pain.

My dad, on the other hand, never complains. My grandmother didn’t complain when she went through breast cancer. My grandfather probably never complained, either.

The internet defines stoicism as:

a philosophy about framing things in terms of what you can and can’t control.

the endurance of pain or hardship without the display of feelings and without complaint.

Keeping it inside

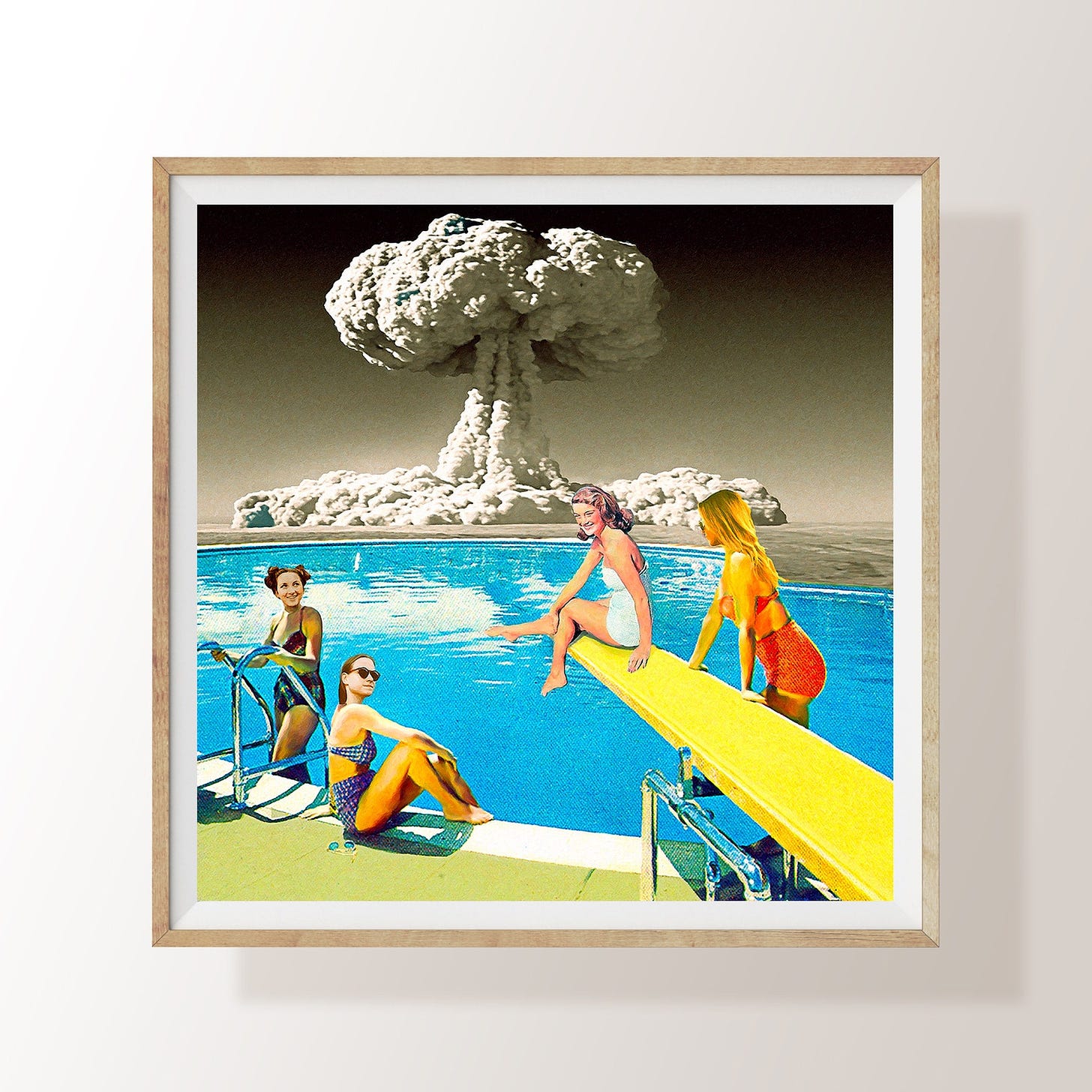

Our culture’s tendency toward stoicism, traditional masculinity roles, and keeping feelings inside isn’t just a Boomer thing. Some friends say they’d prefer their friends keep their shit private as well.

The upshot to bottling up your feelings means you’re more fun at parties. The downside is a massive German study that found keeping fear, anger, or anxiety to oneself boosts the risk for high blood pressure, a serious risk factor for cardiovascular disease, heart attack, and stroke.

Then there is toxic positivity, defined by Psychologist Jamie Long of thepsychologygroup.com as: “the pressure to only display positive emotions, suppressing any negative emotions, feelings, reactions, or experiences.” Toxic positivity can invalidate human experience and lead to isolation and unhealthy coping mechanisms. Some even consider toxic positivity a form of gaslighting because it creates a false narrative of reality, often causing you to question what you think and feel.

Should we just let it all out?

Arthur Brooks wrote an article for the Atlantic titled Why Maybe You Shouldn’t Write a Memoir. He says people like talking about themselves because it causes a small dopamine hit in the brain. However, depressed people talk more about themselves and have difficulty switching their attention to other people and things. His argument claims that “conversational narcissism—especially complaining—drives people away, which can make the mood disorder worse.”

In the essay “In Defense of Navel Gazing” from the book Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative, Melissa Febos counters the argument, citing psychologist James W. Pennebaker’s study that participants who wrote about past trauma made fewer visits to physicians.

“Expressive writing about trauma strengthens the immune system, decreases obsessive thinking, and contributes to the overall health of the writers,” she writes.

Dian Million, in the article “Felt Theory: An Indigenous Feminist Approach to Affect and History,” shows how Native American women wrote personal narratives to explore the racialized, gendered, and sexual nature of their colonization. “In doing so,” Million writes, “they transformed the debilitating force of an old social control, shame, into a social change agent in their generation.”

In this way, memoir writing can reframe the narrative and thereby alchemize shame into empowerment and a sense of agency.

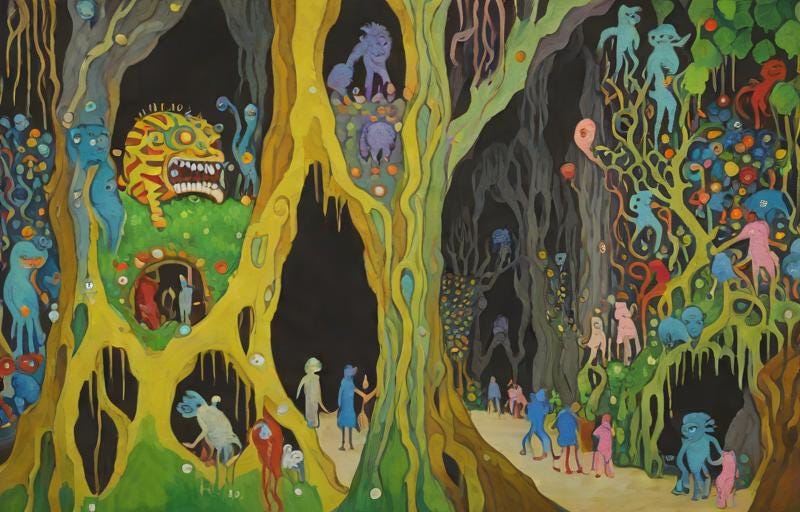

Greeting our monsters

One of my favorite writer-philosophers, Bayo Akomolafe, invokes the monster archetype to see how cultures define moral architecture. We can see how children’s movies in the 80s explored this monster archetype in The Dark Crystal, Legend, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, Never Ending Story, and Godzilla.

Nowadays, however, Godzilla is a smoothed-over, pet-like monster. Whiteness, or mainstream Euro-American culture, prefers to “reduce a tree and its prickly nature to something easier to digest, to reduce everything to a tamer version of itself.”

What was once meant to keep us safe and create belonging ends up having the opposite effect. When a friend doesn’t want to listen or look at my cracks, won’t greet my monsters, won’t venture with me into what my friend calls “the pain cave,” I feel the opposite of safe. I feel the opposite of belonging. I feel like what Akomolafe calls “anexposure,” a surface-level, plastic veneer of performative kinship.

The monster exists at the edges of things, guarding the edges, and is “the agent of shape-shifting.” The danger with stoicism, Akomolafe says, is passivity. If we deny the monster, we deny change.

It’s not that we have to dwell in the shadows, in the cracks, in the mouth of the monster forever. But we have to acknowledge it, greet it, speak with it, try to understand it. That is the only way to move through the pain cave and transform.

“[Refusing] to write your story can make you into a monster. Or perhaps more accurately, we are already monsters. And to deny the monstrous is to deny its beauty, its meaning, its necessary devastation.” - Melissa Febos

To greet our monsters is to greet our fear, our grief. It’s to invite them in so we can show them love, compassion, and light, and eventually send them on their way. It’s so we can catalyze change.

Again, Melissa Febos:

“It is not gauche to write about trauma. It is subversive… I believe that stories like these have the power to transform the world. We are writing the history that we could not find in any other book. We are telling the stories that no one else can tell, and we are giving this proof of our survival to each other.”

Now tell me, are you writing a memoir? If so, how are you approaching your monsters? What are your thoughts about Arthur Brooks’ article?

Tell me in the comments!

Thank you for reading The Feral Stack! If you liked this post, please smash the heart button so more people can discover it.

You can also help support by re-posting this or sharing it with a friend!

Thanks so much, Mike! And if you haven’t already, check out the comments. They could be their own beautiful essay!

Dear Summer -- You are SOOOOOO completely speakin' my language! As a guy who's spent most of his 66 years on Earth recounting stories of horrors both real and imaginary, I've always considered it my job to understand the monster in myself, and in each and everyone.

Horror fiction is the fiction of worst-case scenarios, in which we can frankly address the damage. (Rod Serling created THE TWILIGHT ZONE as a way to get around network censors, because he could put truth in the words of a ghost or an alien that a regular person would be not be allowed to share in between commercials for mouth wash and Ovaltine.)

So when it comes to memoir, are we supposed to shave off the shadows, render ourselves as smiley-face emojis? And then be surprised when the "return of the repressed" takes the form of a fucking heart attack?

I'm as stoic as the next guy who is also a stoic when it comes to dumping my trauma on any poor stranger who haplessly asks, "And how are YOU doing today?" But when it comes to the work, EVERY day is "Take Your Monster To Work Day". I may not give them the megaphone. But I sure as shit don't leave 'em stuck in the car with the windows rolled up.

So THANK YOU for your beautiful piece! I am so glad we stumbled across each other here in Substackland, and will be gleefully reading your thoughts from this point onward. You are awesome.

Yer pal in the trenches,

Skipp