Hello, friends! Hello to those who have been here a while and those just joining! Thank you for reading and subscribing! And deep, deep gratitude to those who opted into a paid subscription.

If this post or any of my posts resonate with you, I highly encourage you to go back and read the comments. They are fire and could write their own book!💕

Recently, I found out the Māori word for autism is taonga takiwātanga, which means “gifted” and “in their own time and space.” Autistic children in Māori culture are seen as possessing a strong spirit and an ability to connect with the higher spiritual realm.

My daughter’s abilities to see the unseeable were always apparent. In utero, her rhythms and movements reflected my thoughts and feelings. As a baby, she clung to me with her whole being.

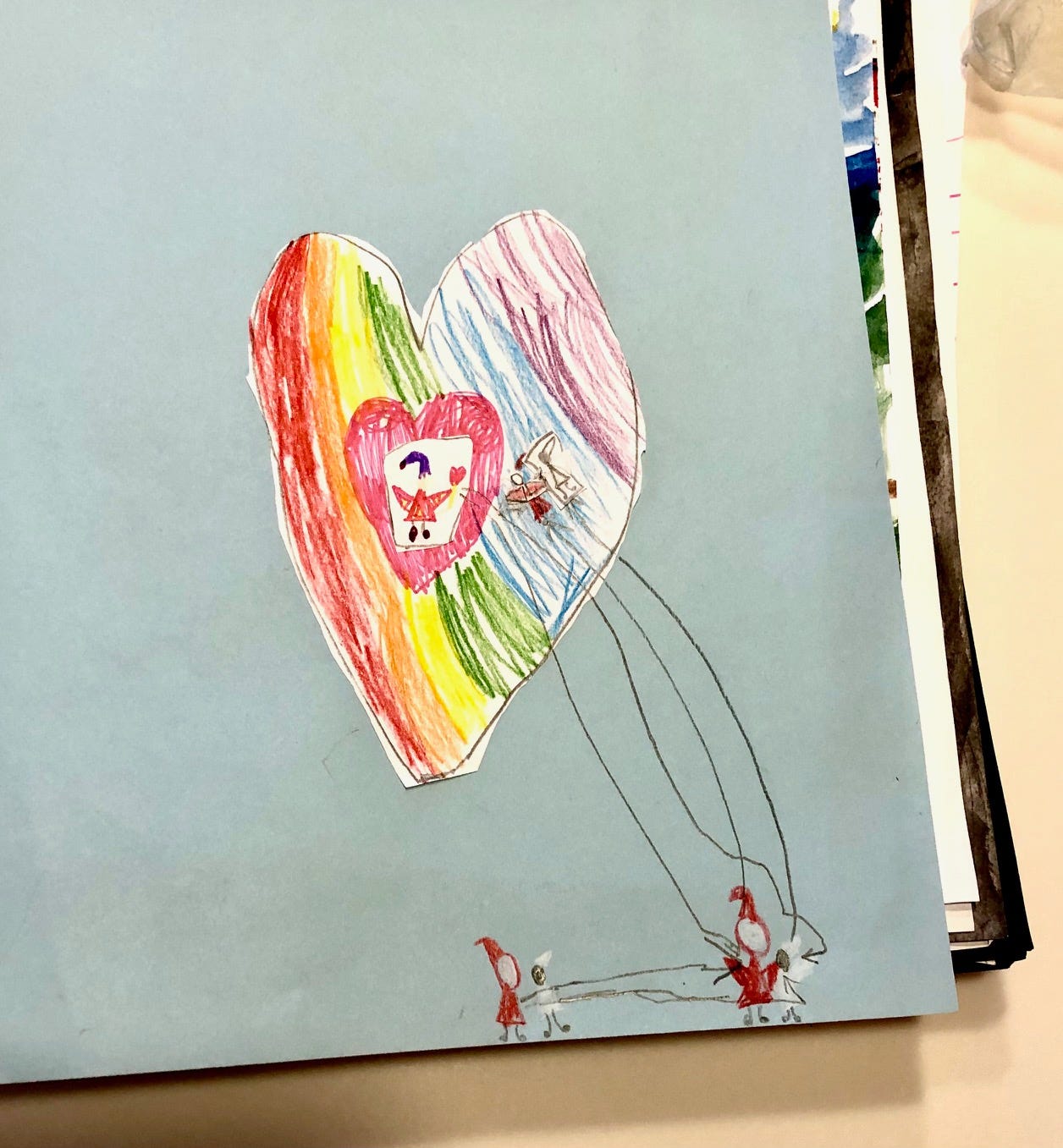

Then pandemic lockdown came, and she “repurposed” appliances and hardware into art, which I wrote about for Insider. She drew characters flying kites in the shape of hearts as if to transmit the message We’re still here! We exist! Send love!

When it was time to return to school, unvaccinated and in masks, she drew people enveloped in scuba suits, breathing with the help of an oxygen tank.

“They’re in acid,” she said. “But the acid grows their wings.” A perfect metaphor for resilience, I thought.

Her pandemic sketches seemed to absorb the collective subconscious and reflect it back to us, like the heart shape of a puppy’s brow and the lung-like detail of a butterfly’s wings.

She must be magickal, I thought. Little did I know that magick had a name: autism.

Like any Spidey sense, my daughter’s powers of absorbing and transmitting soon became too overwhelming. When she returned to in-person school, she pushed children, ran away from school, drew bubbles all over the bathroom, and ripped handwashing posters from the walls. We had her tested for autism, and she was diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

When I received the diagnosis, I felt like I had won the lottery. Yay! It wasn’t shitty parenting, my daughter was simply autistic! I wanted to shout it from the roof! The psychologist, however, advised me not to take out a full-page advertisement and “make a thing out of it.”

But I was proud of my daughter’s uniqueness, so I told her she was “on the spectrum.” I told her that, like indigo, she was a beautiful and unique color that many would mistake for purple, but upon closer observation, was actually the rarest blue. (I wrote about it for the New York Times’ Tiny Stories.)

When the art teacher introduced the color spectrum to her class, my daughter announced: “I’m on the spectrum, too!” Then, she proceeded to explain to the class why all the colors were beautiful, unique, and important.

What culture deems useful (or not)

Writer, philosopher, and teacher Bayo Akomolafe defines cracks as things that have outlived their usefulness.

In our culture, in which “time is money” and is defined by cultural anthropologists as a “rushing river, quickly moving and escaping,” how can a child who is on her own time be anything other than a crack?

In a capitalist culture that values productivity over people and relationship, what usefulness does a girl on her own time with access to the higher spiritual realm serve?

In an educational system modeled after factories, in which subjects and tasks are typically disconnected, inauthentic, and surface level, how can an autistic child who likes to investigate something for hours at a time truly explore and dig deep?

In a patriarchal world where sensitivity is considered a weakness, what kind of value or cultural capital does a highly sensitive girl offer?

“Whiteness polices the cracks” - Bayo Akomolafe

My sixth-grade son has reached the age when conformity means safety. He resents his little sister, who dances in the aisles at church, sings in public bathrooms (while inadvertently summoning ghosts), and has meltdowns in public.

My son is growing up in a culture that polices the cracks, rejects disturbances, and punishes, fears, incarcerates, and pathologizes “the other.” What better place to see this than at middle school, where peers are rejected from the tribe for standing out? (I would know, I teach there.) Even in the cool, dissident circles, even in non-white groups, one still must match the unspoken code.

(P.S., can everyone please stop saying “be yourself”? We’ve seen what happens when people actually start being their authentic selves— they end up friendless, doxxed, unemployed, divorced, or in jail.)

No surprise then that in the United States, autism is classified as a “dis-ability.” It is this naming that betrays the problem. When my daughter’s gift is seen as a deficit, the typical (or neurotypical) response is to “fix” it.

Most autism funding is still funneled towards finding “cures.” In mainstream Euro-American culture, autistic children are taught, explicitly and implicitly, to suppress or “mask” their autistic behaviors.

Last year, my daughter was bullied and called “dumb” by peers (never mind that she scored “exceptionally high” on the IQ test). Playdates with her are typically not initiated or reciprocated. I usually go out of my way to drive, feed, and care for other people’s children so my daughter can spend time with friends.

A report conducted by Ambitious About Autism found that twenty percent of parents claimed their autistic child had been formally excluded from school, while four in ten young people with autism were excluded informally. In the U.S., fewer than half of autistic adults are employed.

In Don’t Mourn for Us, autism advocate Jim Sinclair writes: “The tragedy is not that we're here, but that your world has no place for us to be.”

But what if we approach autism not as a thing to “cure,” but to learn from?

Cracks as invitation

Dominant white culture rewards individuals who possess personality traits and values that encourage productivity. Therefore, it shouldn’t be any surprise that, according to Smithsonian’s "Aspects and Assumptions of Whiteness in the United States,” some of the values held by the culture include:

competitiveness

rationalism

linear thought

goal/future orientation

hustle culture

rigid time schedules

extroversion

don’t show emotion

There are many more, but we’ll start with those. My daughter checks absolutely NONE of those boxes (and, frankly, nor do I, which is why I lived outside the United States for several years).

What should we do with people like my daughter who disrupt, who put a crack in the carefully crafted matrix?

What if we called out the bullshit cultural values that uphold a system that disconnects us from our true nature and instead leaned into the cracks, sat with the disruption, and observed?

Bayo Akomolafe, who also has an autistic child, says that the wisdom lies within the cracks. “We can invite [my son] to mask, and to portray himself as belonging,” he says. “But I want to hold space for the disruption of belonging and the promise of monstrous entities.”

Back in the day, before my ancestors domesticated livestock and land, before people became property, my ancestral elders and visionaries convened worlds around cracks. They looked to cracks and monstrous figures for lessons and wisdom.

While living in the Bay Islands of Honduras with farmers who claimed to have never been colonized, I watched as my Islander friends revered a severely obese and disabled young man, ingratiating themselves to him and beseeching his advice. Similarly, the Navajo view autism as “a beautiful difference,” according to Dr. Anna Wilson with the University of Alberta School of Information and Library Studies. Rather than trying to make them appear more neurotypical, maternal mentors guide autistic relatives into fostering their unique strengths.

What the neurotypical world can learn from autism

Bayo Akomolafe says his son “lives where they are still stitching time.” My daughter lives in a realm beyond clocks. She keeps time with her senses—the rumbling of her stomach, the bending of the light through the trees, the shivering under her coat.

But in this world, “time is money,” and time is “scarce.” We’re always “running out of time.” Time waits for no clairsentient, fey creature.

My daughter’s approach is wild, feral, intuitive, sensorial. She uses colors to describe the feel of things, like music, or the sound of words.

She speaks too loudly because, as one autistic blogger put it, “When it seems like the world is always yelling at you, you yell back.”

She is honest to a fault and is still mad at me for lying about Santa Claus.

She can come across as lacking in empathy because she is always hyper-focused on whatever she is doing. And yet, I can’t listen to the news around her; she gets too upset at the first mention of people suffering. If I squash a mosquito in front of her, she calls me a horrible person, as if she feels their pain as well. My sister feels physical bodily pain when she sees others being hurt, and I believe my daughter does, too.

What kind of world could we co-create if we all felt each other’s pain? If we listened to the color of our words? What kind of politicians would we elect if we were all so honest? (No offense to Santa.) What kind of “progress” could we make toward solving the meta-crisis if we had my daughter’s hyper-focus, creativity, empathy, and stick-to-it-ness?

We need a new approach to autistic education. Instead of placing them in remedial math, as my daughter was this year before I tutored her and she advanced to the highest group, we should give autistic children a rigorous curriculum that allows for in-depth interdisciplinary and creative discovery.

We should learn from autistic people how to become more sensitive. Michael Pluess, a professor of developmental psychology at Queen Mary University of London, argues we need to cultivate more sensitivity in order to develop awareness, empathy, creative thinking, and skills to deeply process and wrestle with the big issues facing us.

In Untamed, Glennon Doyle says that being sensitive is a superpower:

“In most cultures, folks like Tish are identified early, set apart as shamans, medicine people, poets, and clergy. They are considered eccentric but critical to the survival of the group because they are able to hear things others don’t hear and see things others don’t see and feel things others don’t feel. The culture depends on the sensitivity of a few, because nothing can be healed if it’s not sensed first.”

^^^ feeling the music in Red Square on the campus of Western Washington University

How we respond to cracks determines our politics and values

Do we fear and control and police the disruptions? Or ask for a lesson?

“Sit with these cracks as an invitation, as invocation, whether an autistic child or ecotone or moment that has no explanation,” Akomolafe suggests. “By sitting with these moments, we make possible new choreographies, new worlds.”

Sometimes, the lesson is to be more sensitive. Sometimes, it’s to be more present. To listen to the things without words. To give them new language. To dream up new worlds. To create them.

To ask, to listen.

“Those misdirections, those failures might be the heart of a new kind of politics that we need today.” — Bako Akomolafe

If you’re interested in reading from some amazing disabled (not autistic) authors, I highly suggest checking out

, , and Alice Wong with . I recommend reading autistic writer and, of course, Bayo Akomolafe, who isn’t on Substack. If you know of another fabulous autistic or disabled writer, please let me know in the comments!Do you love someone who is “dis-abled?” What do they teach you? What have you learned from the cracks and cosmic disruptions?

Sound off in the comments!

Love,

Summer

P.S. Thank you for reading! If you liked this post, please smash the heart button so more people can discover it.

I'm an autistic writer on Substack, but I won't make any claims about the quality of my writing.

Gosh, I've been pretty down about autism, lately, and I relate so much to everything you said about your daughter. I didn't get to be diagnosed when I was young, and I didn't get to be appreciated for who I was. I'm so grateful that your daughter has you. Thank you so much for posting about her so beautifully.

This is a great article about neurodiversity in general - but also can I point out how nice it is to read about a parent celebrating their child's autism when that is in no way the norm?! This article makes me happy for your daughter. We need more writing like this about the topic.